The “ZipLine” campaign flips the script on traditional phishing by starting with a friendly knock on your front door: your company’s “Contact Us” form. After spending weeks building a rapport designed to shatter your defenses from the inside out, this campaigns attack path is aimed for long term persistence. This sophisticated, multi-stage loader operation primarily targets U.S.-based organizations, moving away from “scare tactics” in favor of patient, psychology-driven deception, through seemingly legitimate business communications.

The goal is to establish a stealthy, long-term in-memory backdoor to enable remote command execution and reconnaissance while avoiding detection by blending with legitimate services.

CyOps has proactively developed new behavioral detections to identify these campaigns in their early stages, with automated prevention capabilities currently being finalized for rollout.

Threat Analysis Overview

The Zipline infection process replaces the typical “smash and grab” approach for malware delivery and instead a slow burn strategy of engagement. The threat actor leverages the target’s own internal communication workflows to ensure by the time the technical execution begins, their guard is already lowered. Victims receive emails containing ZIP attachments that appear to include harmless corporate documents, such as contracts or business proposals. While these files look legitimate, the malicious activity is hidden behind the scenes and is not immediately visible to the user.

Once opened, the ZIP file silently launches a multi-stage process that installs malicious code on the victim’s computer. The attackers deliberately disguise their activity by showing real, benign documents to the user while covertly executing hidden scripts in the background. These scripts are heavily concealed to evade security tools and are designed to adapt to each specific system they infect.

The campaign uses trusted cloud infrastructure, including legitimate hosting platforms, to communicate with attacker-controlled servers. This allows the malicious traffic to blend in with normal internet activity and makes detection more difficult. Additionally, the attackers establish persistence on the system, ensuring the malware can survive reboots and remain active over time.

Zipline Attack Chain

Stage 1 – Email & ZIP Delivery [T1566.001]

The infection typically begins with a phishing email containing a ZIP archive attachment. Unlike classic macro-enabled Office documents, the malicious logic in ZipLine is not embedded in the document itself, instead, it’s hidden in the ZIP file’s code.

- The ZIP file uses filenames that resemble legitimate corporate content, for example:

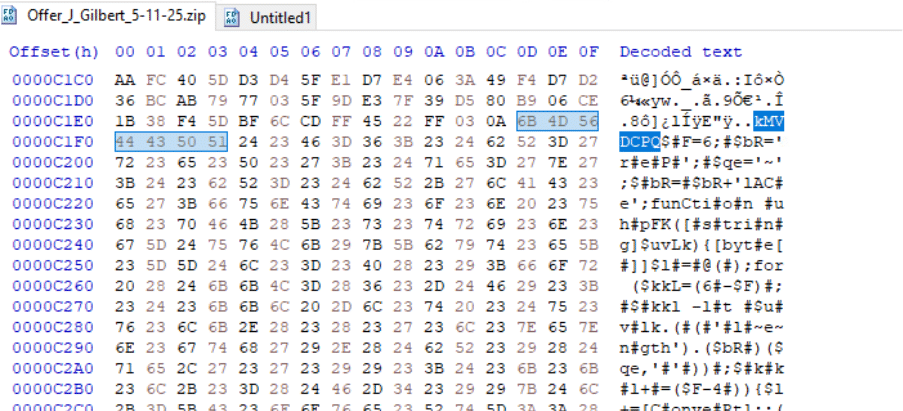

Offer_J_Gilbert_5-11-25.zip

OFFER_GILBERT_115\Brief_WALMART_UK_Expansion_Invitation_5p.docx

OFFER_GILBERT_115\Offer_J_Gilbert_5-11-25.docx.lnk

- A benign-looking DOCX file is included alongside a Windows LNK shortcut within the ZIP archive. After extraction, the LNK serves as the primary execution trigger. When clicked by the user, the shortcut launches a PowerShell command-line that locates and processes the extracted ZIP content.

- While the DOCX file functions purely as a decoy to reinforce legitimacy, the LNK is responsible for initiating the malicious execution chain by extracting and dynamically reconstructing the embedded PowerShell stages hidden within the ZIP.

Attackers likely rely on user interaction to extract and click the decoy or shortcut.

Stage 2 – PowerShell Loader (Obfuscated) [T1059.001, T1027]

Once the ZIP is extracted and executed by the LNK file, a heavily obfuscated PowerShell script runs. This script is designed to:

- Locate the malicious ZIP in user folders (Downloads and ProgramData).

- Extract its contents into a staging directory

C:\ProgramData\Offer_J_Gilbert_5-11-25.zip\

- Perform runtime de-obfuscation of the subsequent stage.

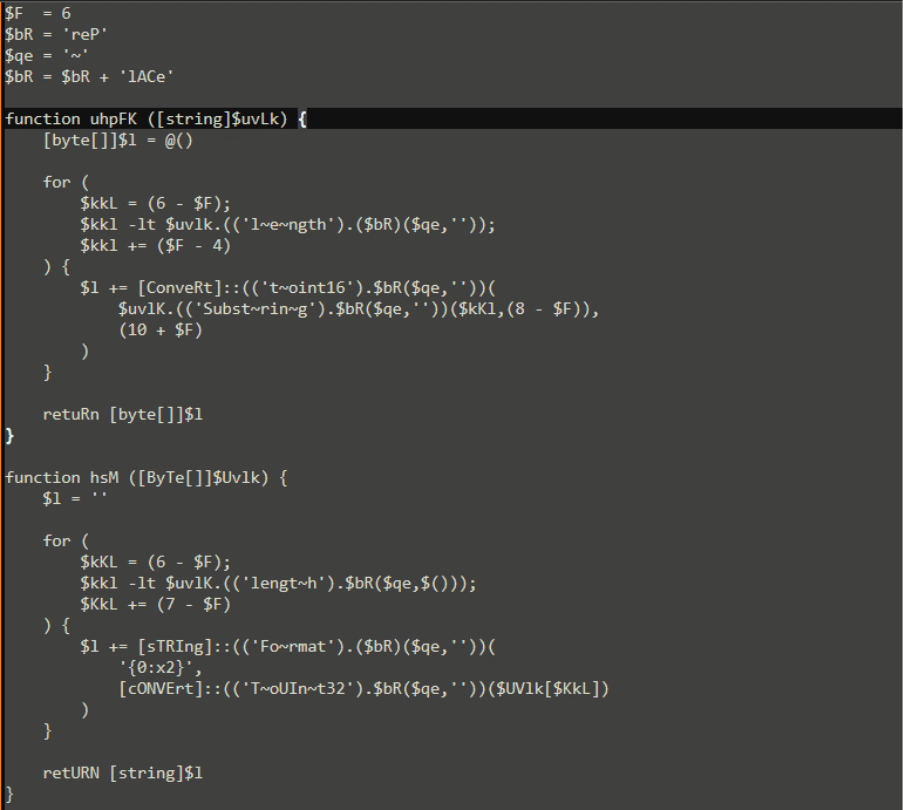

All strings in this script (function names, type names, APIs) are assembled dynamically using techniques:- Dynamic string re-construction

- Strings are stored in fragmented or altered form and rebuilt at runtime.

- Character replacement-based decoding

- Obfuscated strings are normalized at execution using repeated string replacement operations.

- Delayed API resolution

- .NET classes, methods, and properties are resolved only during execution rather than being referenced directly.

- Reflection-based invocation

- Methods and fields are accessed dynamically through .NET reflection instead of static calls.

- Runtime method name construction

- Method names are assembled from multiple string components before invocation.

- Indirect execution flow

- Execution paths are determined dynamically, making static control-flow analysis unreliable.

- In-memory stage reconstruction

- Subsequent script stages are rebuilt entirely in memory rather than written as standalone files.

- Dynamic string re-construction

- Bypass AMSI

- The Anti-Malware Scan Interface, using reflection to flip an internal AMSI boolean.

- This effectively disables PowerShell’s built-in script scanning before executing deeper code.

- Search for an embedded marker

- (e.g., kMVDCPQ) within the extracted ZIP. The following commands then rebuild the next payload using this marker:

And after cleaning the file’s code from “#” symbol:

Stage 3 – Decoder & Runtime Logic [T1140, T1071.001]

The next stage: reconstructed at runtime, contains:

- Multiple decoding functions

- Hex string to bytes

- XOR-based transformations

- Custom CRC-like and formatting routines

- A flexible HTTP downloader

- Uses .NET System.Net.WebClient configured to accept TLS 1.2/1.3

- Adds realistic headers (e.g., User-Agent for Chrome)

- Honors system proxy settings

- Wraps download calls in try/catch

These functions are used to decode remote content and convert it into executable commands.

Stage 4 – Persistence & C2 [T1053.005, T1071.001]

Once the decoded loader executes, it attempts to establish persistence:

- It constructs a unique Scheduled Task name based on host identifiers (e.g., Windows Productid hashed into a task/mutex identifier).

- If the task isn’t present, it registers a scheduled daily task at 11:00 AM, using explorer.exe to launch the .lnk file.

- This technique blends with normal system behaviour and avoids direct PowerShell invocation.

- A global mutex is used to enforce single-instance execution.

In the continuous loop that follows:

- The script randomly sleeps between iterations.

- It constructs a beacon URL, which combines:

- A base URL hosted on Heroku’s Platform-as-a-Service

- https://supplier-desk-8a887a3fd9de.herokuapp.com/

- Host-specific identifiers and random components

- It performs HTTP GET requests to this URL, effectively acting as a C2 beacon.

If the server responds with a structured response containing encrypted command segments, the script performs:

- A split on dot (.)

- A check for expected length

- Decryption via custom functions

- Dynamic execution using PowerShell (often via an IEX-equivalent built at runtime)

This results in arbitrary incoming commands being run on the victim host.

Cynet vs ZipLine Campaign:

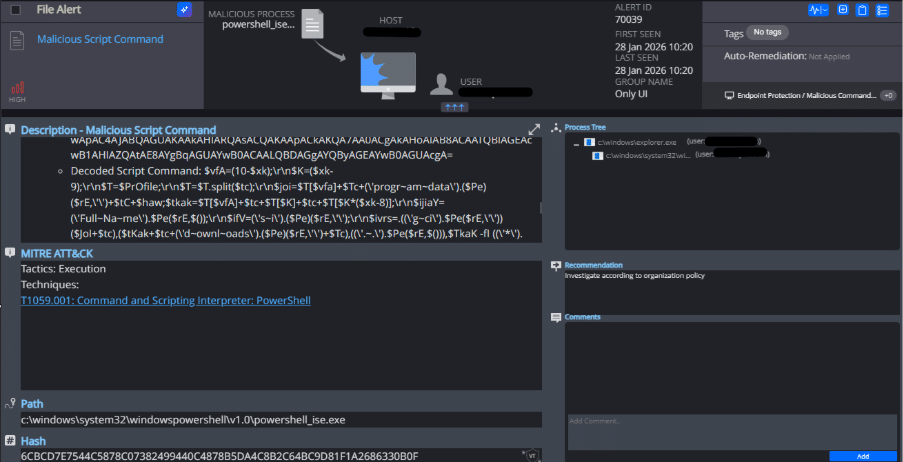

In this case, Cynet successfully detected the ZipLine attack at its earliest execution point, before the multi-stage infection chain could fully unfold:

When the user executed the malicious LNK file extracted from the ZIP archive, the embedded PowerShell command was invoked. At this point, Cynet’s AMSI-based inspection intercepted the script during runtime execution.

Despite the heavy obfuscation employed by the attacker, Cynet was able to:

- Trigger an alert at the first stage of execution

- Detected the malicious PowerShell script execution and presented the executed script content directly within the alert

- Identify the malicious behavior as PowerShell-based execution rather than relying on static signatures

The detection did not rely on the final payload, command-and-control communication, or persistence activity. Instead, Cynet identified the malicious behavior at the initial execution stage, when the LNK-triggered PowerShell code began running, allowing the attack to be stopped before any meaningful impact or later stages were reached.

Defensive & Technical Observations

Evasion Techniques

- Obfuscated string reconstruction defeats static string scanning.

- Reflection-based AMSI bypass prevents host AV/EDR from inspecting deeper stages.

- Embedded stage marker means the “real” malicious code is not present in a static file form.

Indicators of Compromise

- Presence of ZIP folder under ProgramData named with .zip suffix.

- sha256 of the zip file: c4c09a52633ea6174a5238924413a38908aa0014e9fc39265c679d8a7296040b

- Scheduled Tasks calling explorer.exe on .lnk decoys.

- PowerShell heavily using .Replace() string assembly.

- Outbound HTTP to Heroku-hosted domains with random path components.

- URL for example: hxxps://supplier-desk-8a887a3fd9de[.]herokuapp[.]com/32894e104ade0000

Infrastructure Misuse

- Using legitimate cloud services (Heroku) enables attackers to blend malicious C2 with benign infrastructure.

- Frequent domain rotation and PaaS hosting complicate static blocklist efficacy.

Conclusion

The Zipline campaign highlights a shift toward patient, high-rapport social engineering that prioritizes long-term access over immediate damage. For critical industries such as manufacturing and supply chain-based sectors, this measure of “persistence”, is especially concerning. CyOps’ goals for detection capabilities lie in the ability to identify these stealthy loaders in this multi-stage attack before that permanent foothold is established. Overall, ZipLine represents a stealthy and well-engineered threat rather than a simple phishing attempt. Its design indicates a focused effort to avoid detection, maintain long-term access to infected systems, and potentially deliver additional malicious payloads at a later stage. For MSPs, this campaign is a reminder that “trust” is a primary attack surface that requires context-aware security to defend effectively.