Achieved 100% protection in 2024

Stop advanced cyber

threats with one solution

Cynet’s All-In-One Security Platform

- Full-Featured EDR and NGAV

- Anti-Ransomware & Threat Hunting

- 24/7 Managed Detection and Response

By: Shiran Grinberg

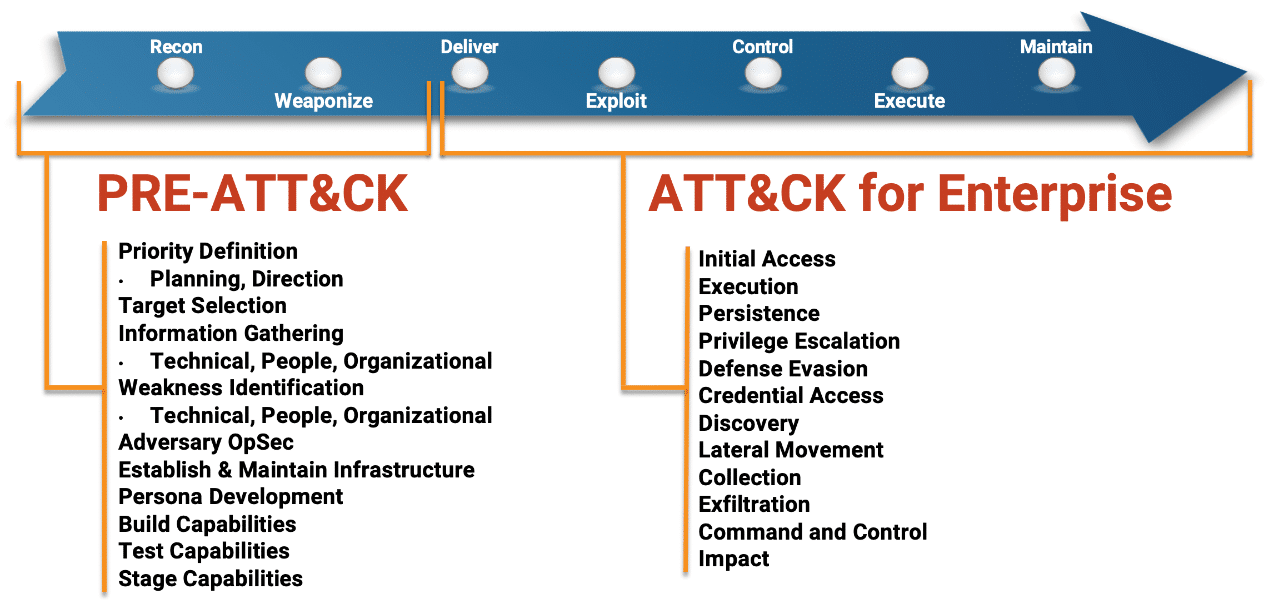

In recent articles we’ve seen how adversaries can gain initial access to a network utilizing Office Macro Attacks, and how Responder can be used to steal credentials, escalate privileges and move laterally in a network. Initial access, privilege escalation and lateral movement are three key components of Enterprise attacks – but there’s more to it.

Much more, in fact: according to MITRE’s adversary model, Enterprise attack methodologies can be divided into 12 subcategories, representing different phases of a campaign’s life-cycle. In this series, we will go through different attack methodologies and tools, explain their role in the grand scheme of cyber network operations, and discuss options for risk mitigation.

Figure :1 MITRE’s ATT&CK for Enterprise Adversary Model

Today’s article touches on C&C Communication and Data Exfiltration. Having some form of control and exfiltration interface with targeted machines is a vital part of most cyber campaigns, and it may seem rather straightforward. After all, C&C is essentially a form of endpoint communication between the victim and the attacking machine – and endpoint communication is one of the most basic functions of any modern machine.

But as security threats advanced over the years, so has the security-solutions landscape. From Firewalls, Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDS & IPS) and Security Information and Event Management Systems (SIEM) to User and Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA), Stateful Protocol Analysis and Steganography – traffic monitoring is growing ever-tighter and attackers are forced to find novel ways to remain undetected.

This is part of an extensive series of guides about Network Attacks

One mainstay method for traffic obfuscation is Protocol Tunneling (MITRE T1572: Protocol Tunneling[1]). When tunneling a protocol, instead of explicitly sending data packets in a protocol of choice (say TCP), adversaries will encapsulate the packets within another protocol. This behavior aids in concealing malicious traffic inside seemingly innocuous communication forms, aiding in detection evasion. Furthermore, it can be used to encrypt data and protect the attacker’s identity and interests.

Aside from creating a covert C&C and data exfiltration channel between two machines, protocol tunneling can also be used to bypass captive portals for paid Wi-Fi services. Many times, portal systems will block most TCP and UDP traffic to/from unregistered hosts – but will allow other protocols such as ICMP, DNS etc. Adversaries can exploit this by tunneling their traffic inside an allowed protocol’s packets.

Expanding on traditional protocol tunneling, hackers may use non-application-layer protocols, which are generally deemed less likely to be monitored for malicious intents, to obfuscate their traffic.

One common form of non-application-layer protocol tunneling is ICMP Tunneling.

The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) is an OSI Network Layer protocol, used to discover and control routing problems across a network. When certain errors are detected by networking devices, they will produce ICMP packets to inform endpoints about what happened.

In example, when a routing loop occurs in a network, IP packets will circle endlessly across the loop, and eventually their TTL value will drop to zero. At this point, the last router to receive the packet will send an ICMP “Time Exceeded: TTL expired in transit” message to the packet’s source IP.

ICMP messages can also be used to control routing. For instance, if an endpoint sends a packet through an inefficient route, routers along the way may detect this behavior and send an ICMP “Redirect Message” packet – which will suggest a better route to be used next time.

Generally speaking, this protocol is not implemented on endpoint machines, aside for two very well-known tools:

Remember how ping uses ICMP Echo packets to test host reachability across a network? Basically, the pinging host will send an Echo packet with some data to the pinged host. Then, the pinged host will answer with an Echo Reply containing the same data. The data may be arbitrary and no strict guidelines are defined is ICMP’s RFC.

Attackers can exploit this design choice to obfuscate malicious network behavior. Instead of explicitly communicating with a machine in the protocol of choice, each packet will be injected into an Echo or Echo Reply packet. The communication stream will now seem to be a series of ping operations, rather than, for instance, a TCP connection.

ICMP’s intended use is for discovering and controlling networking issues, so its de-facto ability to establish a data channel between two machines is often overlooked. Moreover, being that ICMP is an essential, well-established part of the Internet Protocol Suite and a non-Application-Layer protocol, enterprises are less likely to monitor it as closely as the usual data exfiltration suspects – HTTP, HTTPS, TCP, IMAP etc.

Moreover, mitigation is not trivial, being that in many cases ICMP functionalities cannot be completely disabled without impacting user experience significantly.

There are several common toolkits to tunnel traffic through ICMP, and each of them provides slightly different features. Let’s examine them.

Icmpsh is a simple toolkit for running reverse shells on Windows machines. It’s comprised of a client that is written in C and works on Windows machines only, and a POSIX-compatible server that’s available in C, Python and Perl.

Some of icmpsh’s notable features are:

Unlike icmpsh, which is used for C&C, ptunnel is intended for TCP traffic obfuscation and tunneling. When executed, ptunnel’s client will tunnel TCP over ICMP to the designated ptunnel server. The server will act as a proxy, and will forward the TCP packets to and from their actual destination. This toolkit can run on POSIX-compliant OS’s only.

Some of ptunnel’s features are:

Icmptunnel has a somewhat similar architecture to that of ptunnel, but unlike the latter it can tunnel any IP traffic. Additionally, it will tunnel all of the client’s IP packets – and not just a single session, port etc. This makes this tool very useful to bypass captive Wi-Fi portals, but somewhat less beneficial for coordinated cyber-attacks. Both the client and the server need to be POSIX-compliant.

Some of icmptunnel’s notable features are:

Tips From the Expert

In my experience, here are tips that can help you better defend against C&C communication and data exfiltration through advanced tunneling techniques:

In this demonstration we will use icmpsh to tunnel a reverse shell session between our attacking Kali Linux machine and a victim Windows 10 machine.

We chose icmpsh because it doesn’t require administrative privileges to run on the victim’s machine, and is very portable.

Figure 2: Demonstration network’s diagram. Attacker at 192.168.68.113, victim at 192.168.68.115.

Before running icmpsh, we will need to prevent the kernel from replying to ICMP echo requests. Most ICMP tunneling tools will implement mechanisms to synchronize the data stream between the two machines, and the kernel replies may cause unexpected results.

To disable kernel ping replies, we added the following line to the /etc/sysctl.conf file: net.ipv4.icmp_echo_ignore_all=1.

Figure 3: Editing sysctl.conf file to disable kernel Echo replies

First, we will run the icmpsh server on our Kali Linux machine. Thankfully this tool is very easy to use and only requires two arguments: the attacker and the victim’s IP addresses.

Figure 4: Running the icmpsh server on a Kali Linux machine.

Our machine is waiting for ping requests from our victim, 192.168.68.115.

Now we can run the client, which is an executable file that can be downloaded from the GitHub page linked above. Here are its arguments:

Figure 5: Available arguments for icmpsh’s Windows client executable

Our Kali machine is at 192.168.68.113, so this is the final command:

Figure 6: Running icmpsh client on Windows 10 machine.

On the attacking side, we are starting to receive SSH data:

Figure 7: Icmpsh server displaying client’s reverse shell output.

Now that everything is set up, we have a functioning reverse shell on our Kali server. For example, we can type systeminfo to gather information on our victim’s machine:

Figure 8: Running systeminfo through icmpsh’s reverse shell

When inspecting the network traffic between the two machines, we can see the extensive amount of ICMP packets:

Figure 9: Extensive ICMP traffic between the attacker and the victim, as captured on Wireshark once a reverse shell was initiated.

Additionally, as icmpsh doesn’t encrypt the data, we can see the shell’s text injected inside the datagrams:

Figure 10: Plaintext reverse shell output (marked in blue) obfuscated inside an ICMP packet.

Generally speaking, ICMP traffic cannot be blocked completely, so mitigation should focus on minimizing risks through network and endpoint detection measures.

Cynet’s network defense products implement smart heuristics and machine learning algorithms to detect and prevent ICMP tunneling. Some common tunneling patterns that may be detected are:

Furthermore, in addition to conventional detection techniques, which rely on centralized traffic analysis through firewalls, IPS systems etc.[2], Cynet’s products can detect and prevent tunneling attempts directly on endpoints, without the need for designated network devices.

Search results for: